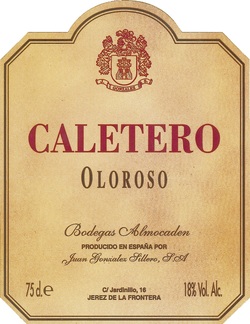

If Fino and Manzanilla are the Princes of wine, then Oloroso is the Emperor. It is sublime and powerful on the nose and on the palate. Its impact on the senses is swift and powerful and is almost offensive the first time one tries to approach it, yet it is also subtle and profound when sipped and paired with food. Logically I should first discuss Amontillado rather than Oloroso as Amontillado is “completed Fino,” but as Fino and Manzanilla have a pure biological development, Oloroso has a pure oxidative development and it will be easier to understand the other types of wine this way. There are different stories as to how Oloroso is selected: that it’s the must that didn’t pass muster to be Fino or that it’s the last pressing of the grape. Actually none of these two things are traditionally true or should be the qualifying factor for what becomes Oloroso. It is suggested that of the three villages in the Sherry triangle, Jerez, far and away, makes the best Oloroso. It is suggested that this is because the grapes from “la Campiña Jerezana” produces a fuller grape. This may well be an old wives tale, what is true is that of all the Oloroso’s I have tasted, the best have come from Jerez. Oloroso was traditionally selected during the early post fermentation stages when the must was allowed to sit in large barrels and be classified. The classifications were made using signals on the barrels. The barrels where “flor” began to grow was marked with a /, called a “raya,” and sent off to be “Fino.” The must where “flor” did not grow, was clearly must that could not become “Fino” and so was reserved for pure oxidative development, as Oloroso. Today, most Oloroso is selected from the first and second pressing of the grapes, the “yema” being reserved for Fino.  If this must does not have flor and begins to age it must be protected from spoilage in the process. There are traditionally only two ways to protect wine from spoilage over time, add sulfur or add alcohol. Fortunately for us, the jerezanos chose to use alcohol. Alcohol was the easy choice. The Berbers that occupied Spain for several centuries brought the ancient science of distillation that they had learned from the Egyptians and had applied it to things other than water. Therefore, the production of alcohol distillate had been going on in Spain for a very long time when the need to add it to Oloroso occurred. The added alcohol allowed the Oloroso to be aged for many, many years without ever spoiling as well as making it extremely resilient to temperature changes. As this added alcohol is added at the beginning of the process, it becomes fully integrated into the wine and there is no heavy alcohol on the nose or on the palate.  From that point the Oloroso begins its journey through the bodega. It goes through the Criadera and Solera process just as the fino does. This process can be as short as three years or as long as one wants. The longer the time spent in the criaderas the better the final product will come out. Unlike Fino, where the wine is passed from Criadera to Criadera approximately a year apart, Oloroso can stay many years in a Criadera without being moved. As this wine has a pure oxitative development, it develops a deep mahogany color and takes on some of its flavor profile from the wood of the barrel.  Oloroso is perfectly paired with red meat, stews and big game. Wild Boar stew with an aged Oloroso is a typical paring here in Andalucia in the roadside “Ventas” in the fall and winter.

1 Comment

|

AuthorPeter De Trolio III Archives

April 2013

CategoriesAbout the Author

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed