|

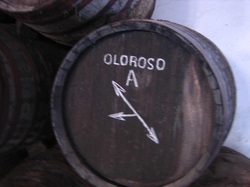

By Peter "Jerez Hound" De Trolio III Sherry is wine. It is not a liqueur. It is not a spirit. It is a fortified wine. It is a complex, aged wine from a very small region in southern Spain. It is painstakingly created through a blend of time, art and nature to make one of the most misunderstood, underpriced liquids of all time. In short, it does not have to be your grandmother's sherry. So now that we’ve gotten that out of the way, what makes it special? As many already know, to drink sherry is to love it. It has a range of tastes that offer something for everyone. These wines go from light straw colored fino to dark and brown Oloroso. Four distinctive types of wine are made from one grape varietal, the Palomino. It is the only wine that goes perfectly with all the "unpairables" — namely anything pickled, olives, asparagus and egg dishes. Each and every one of them a jewel in itself. Where Sherry Comes From True Sherry can only be made in a small triangle of villages: Jerez de la Frontera (from which it derives its name), El Puerto de Santa Maria (which gave us Columbus’ flagship), and Sanlucar de Barrameida. The Marquis de Bonanza perfectly defends confining sherry to this geographical region in his seminal work Jerez – Xerez- Sherry written in 1932. In this book he shows that the word Sherry is a corruption of the Moorish word for Jerez or Sherish and so the name itself defines the wine as coming from this region. How It’s Made: Bodegas and The Solera System The process by which Sherry is made sounds complicated, but it is actually quite straightforward. It begins with first run juice from the Palomino grape, fermented into “Mosto.” The fortification happens early in its process so that the vinic alcohol added is perfectly blended.  Unlike other wines, sherry is not made in the vineyard but in the great “Cathedrals of Wine” Bodegas. In the mid-19th century, these magnificent Bodegas were built throughout the city with vaulted ceilings, interconnected patios and high windows. These windows are left open but covered with shades, allowing for hot and cool zones within one giant room. The barrels, or Botas, are elegantly balanced three high by skilled workers to expose the wines within them to a range of temperatures which produces consistency and depth.  The wine is stored in ancient 500 liter "Botas" American oak barrels many over a century old and blended using the Solera System. Year after year, the top 1/3 of each barrel is removed and blended with wines from previous years. The Botas are then marked with ancient symbols allowing the workers to track which barrels contain which wines. Only after at least three years of such fractional blending can it be called Sherry. When the mosto enters the Bodega it is classified by quality, the most refined being selected for Fino and the bigger, bolder wine being selected as Oloroso. From there this Mosto will begin its journey to maturity. Some of this will become wine that will be bottled and released within 3 years and some of it may wind up aging and aging for generations and not be released until it is 100 years old. Whatever the case, it will always remain in its Botas and never be bottled until it is ready to be shipped.  The result of this traditional type of aging, required by the Consejo Regulador, is a wine with great power that remains subtle and elegant. This is a wine that has been governed by strict regulations for centuries which were codified in 1483. Over time these regulations have been changed and adjusted but have remained fixed now for almost 200 years. This is a wine that accompanied Columbus on his great voyage of discovery, a wine that captured the hearts and minds of the court of Elizabeth I of England after the sack of Cadiz in the late 16th Century, and a wine that was an absolute necessity in the fine parlors throughout Europe during the 19th and 20th centuries. No matter how you look at it, Sherry/Jerez/Xerez is a wine that is irreplaceable and unrepeatable.

1 Comment

|

AuthorPeter De Trolio III Archives

April 2013

CategoriesAbout the Author

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed