“The rain in Spain falls mainly…….” in the south? Not quite what Profession Higgins tried to teach Eliza Doolittle, but it certainly represents the strange truth of this year’s weather. It has rained more this winter than it normally does in three years. As well, it was a very mild winter temperature wise. So a very rainy March along with a soft, rainy winter makes for some seriously thick “flor.” Now, in the Springtime the “flor” is always thick, as the softer temperatures and the rain create the perfect atmosphere for the “flor” to prosper. With the additional rain, the humidity is more constant and the “flor” grows thicker. The thicker the “flor” the greater the protection from the oxygen and the more refined the color will be. As well, the breadiness on the mouth also comes from the “flor,” those flavors should also be more pronounced this Spring. These conditions are very similar to what we experienced this past fall – both unusually wet and mild. So we should see similarities in the taste and texture of the wines. So here’s a great recipe for the spring with clams: Almejas a la Marinera

0 Comments

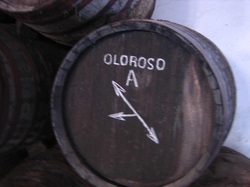

If Fino and Manzanilla are the Princes of wine, then Oloroso is the Emperor. It is sublime and powerful on the nose and on the palate. Its impact on the senses is swift and powerful and is almost offensive the first time one tries to approach it, yet it is also subtle and profound when sipped and paired with food. Logically I should first discuss Amontillado rather than Oloroso as Amontillado is “completed Fino,” but as Fino and Manzanilla have a pure biological development, Oloroso has a pure oxidative development and it will be easier to understand the other types of wine this way. There are different stories as to how Oloroso is selected: that it’s the must that didn’t pass muster to be Fino or that it’s the last pressing of the grape. Actually none of these two things are traditionally true or should be the qualifying factor for what becomes Oloroso. It is suggested that of the three villages in the Sherry triangle, Jerez, far and away, makes the best Oloroso. It is suggested that this is because the grapes from “la Campiña Jerezana” produces a fuller grape. This may well be an old wives tale, what is true is that of all the Oloroso’s I have tasted, the best have come from Jerez. Oloroso was traditionally selected during the early post fermentation stages when the must was allowed to sit in large barrels and be classified. The classifications were made using signals on the barrels. The barrels where “flor” began to grow was marked with a /, called a “raya,” and sent off to be “Fino.” The must where “flor” did not grow, was clearly must that could not become “Fino” and so was reserved for pure oxidative development, as Oloroso. Today, most Oloroso is selected from the first and second pressing of the grapes, the “yema” being reserved for Fino.  If this must does not have flor and begins to age it must be protected from spoilage in the process. There are traditionally only two ways to protect wine from spoilage over time, add sulfur or add alcohol. Fortunately for us, the jerezanos chose to use alcohol. Alcohol was the easy choice. The Berbers that occupied Spain for several centuries brought the ancient science of distillation that they had learned from the Egyptians and had applied it to things other than water. Therefore, the production of alcohol distillate had been going on in Spain for a very long time when the need to add it to Oloroso occurred. The added alcohol allowed the Oloroso to be aged for many, many years without ever spoiling as well as making it extremely resilient to temperature changes. As this added alcohol is added at the beginning of the process, it becomes fully integrated into the wine and there is no heavy alcohol on the nose or on the palate.  From that point the Oloroso begins its journey through the bodega. It goes through the Criadera and Solera process just as the fino does. This process can be as short as three years or as long as one wants. The longer the time spent in the criaderas the better the final product will come out. Unlike Fino, where the wine is passed from Criadera to Criadera approximately a year apart, Oloroso can stay many years in a Criadera without being moved. As this wine has a pure oxitative development, it develops a deep mahogany color and takes on some of its flavor profile from the wood of the barrel.  Oloroso is perfectly paired with red meat, stews and big game. Wild Boar stew with an aged Oloroso is a typical paring here in Andalucia in the roadside “Ventas” in the fall and winter. Fino is the Prince of all wine and Manzanilla is its brother. Both are elegant, refined and dignified while remaining forceful. They are crisp, clean, and sharp on the palate. Having only tertiary flavors, they hit the senses like a ton of bricks. One’s initial reaction to the first glass is usually one of shock, as the flavors cause a sensory overload. Then, after the shock, the palate begins to appreciate the multitude of flavors and the refreshing feeling on the back palate. This is the wine that combines with the unpairables, with egg dishes, olives, pickles and every type of seafood and shellfish.  Fino de Jerez or Fino Sherry is not to be confused with wines called “fino” from other wine producing regions. For centuries wines were given type names without any control or guarantees. The word “fino” simply means refined, so that any wine that was considered as such was so-called. This has lead today to much confusion, as no current wine control organization will make one of their wines change its name. Suffice it to say that the famous “fino” is Fino de Jerez. Yet there is much confusion today with Fino from Montilla-Moriles. Although a nice wine in itself the only thing it shares with Fino de Jerez is its name. It is made from a different grape using a different process and shares none of the qualities as its namesake from Jerez.  Manzanilla shares the same process of “crianza” with Fino but has very specific differences that cause it to be a different type of wine. The first and most important difference is that, within the Sherry triange, Manzanilla can only be made in Sanlucar de Barrameida. The proximity to the sea gives the Manzanilla a saline quality that Fino does not have. Further, the greater humidity in Sanlucar causes the “flor” to be much thicker during the months of extreme temperature, protecting it better from oxidation. Therefore the biological development is different. As a result, the Manzanilla is lighter than Fino. This wine has a very different nose than fino. The reason that it is called Manzanilla is that it smells like the tea manzanilla, the Spanish name for Camomile. The rest of the process is the same for the two types of wine therefore I will refer only to Fino throughout the rest of the article.  Fino is allowed to happen. It is guided by a loving and knowing hand during its evolution, but, not withstanding it is allowed to develop as it will. Immediately after the fermentation process the “mosto” that is deemed most appropriate by the “capataz” is selected to be fino. At that time, vinic alcohol is added to the mosto in order to raise its alcohol level from its natural 12% to 15% in order to create the optimal conditions for the “flor” to grow. At this point in development it can be referred to as “sobretablas” because it is the first time that it will touch wood. It is then added to the last “criadera,” literally nursery, to begin its long development into wine.  As soon as the mosto reaches 15% alcohol a naturally occurring yeast, called “flor,” begins to grow. This is the main reason that Sherry cannot be made outside the Sherry triangle, this “flor” exists nowhere else in the world and cannot be transplanted. This yeast has a symbiotic relationship with the wine; it feeds the wine and the wine feeds it. This yeast feeds off oxygen and alcohol, keeping the wine from a natural rise in alcohol as a result of evaporation and it protects the wine from oxygenation. This allows the wine to remain a very light straw color.  The “flor” and the wine are revitalized by moving part of the wine from barrel to barrel or “rociando.” This wine movement is done once or twice a year depending on when the wine “asks” to be moved. This is a process of dynamic, fractional blending: that is, 1/3 of the content of the wine barrels in one stage is removed and added to the barrels in the next stage (criadera), as an equal fraction from that stage has been removed and added to the next, this done until one gets to the “criadera” from which the bottling takes place (called the “Solera”). The wine moves and the barrels are always stationary. The wine being moved refreshes the wine in the barrel into which it is moved and the wine currently in that barrel “educates” the new wine just added. This process allows the wine to be always ancient yet always new. It creates a wine that is consistent, and fresh and young no matter how old the “Solera,” or base wine, is.  This is a wine that speaks to those who understand how to listen to it. The “capataz” which is translated as overseer, is the man responsible for listening to the wine and seeing to it that its wishes are fulfilled. He is the man who decides when it is time to move the wine from one criadera to the other. He is the guiding hand that helps what is a natural process come to fruition. An expert capataz is one that makes, rather than a good wine, a great wine. Fino and Manzanilla, then, are a combination of wine, flor, capataz and bodega. It is the art of the capataz combined with nature, unique and non-transferable. Sui generis. Fino VS Manzanilla: Pairing the Unpairables

By Peter "Jerez Hound" De Trolio III Sherry is wine. It is not a liqueur. It is not a spirit. It is a fortified wine. It is a complex, aged wine from a very small region in southern Spain. It is painstakingly created through a blend of time, art and nature to make one of the most misunderstood, underpriced liquids of all time. In short, it does not have to be your grandmother's sherry. So now that we’ve gotten that out of the way, what makes it special? As many already know, to drink sherry is to love it. It has a range of tastes that offer something for everyone. These wines go from light straw colored fino to dark and brown Oloroso. Four distinctive types of wine are made from one grape varietal, the Palomino. It is the only wine that goes perfectly with all the "unpairables" — namely anything pickled, olives, asparagus and egg dishes. Each and every one of them a jewel in itself. Where Sherry Comes From True Sherry can only be made in a small triangle of villages: Jerez de la Frontera (from which it derives its name), El Puerto de Santa Maria (which gave us Columbus’ flagship), and Sanlucar de Barrameida. The Marquis de Bonanza perfectly defends confining sherry to this geographical region in his seminal work Jerez – Xerez- Sherry written in 1932. In this book he shows that the word Sherry is a corruption of the Moorish word for Jerez or Sherish and so the name itself defines the wine as coming from this region. How It’s Made: Bodegas and The Solera System The process by which Sherry is made sounds complicated, but it is actually quite straightforward. It begins with first run juice from the Palomino grape, fermented into “Mosto.” The fortification happens early in its process so that the vinic alcohol added is perfectly blended.  Unlike other wines, sherry is not made in the vineyard but in the great “Cathedrals of Wine” Bodegas. In the mid-19th century, these magnificent Bodegas were built throughout the city with vaulted ceilings, interconnected patios and high windows. These windows are left open but covered with shades, allowing for hot and cool zones within one giant room. The barrels, or Botas, are elegantly balanced three high by skilled workers to expose the wines within them to a range of temperatures which produces consistency and depth.  The wine is stored in ancient 500 liter "Botas" American oak barrels many over a century old and blended using the Solera System. Year after year, the top 1/3 of each barrel is removed and blended with wines from previous years. The Botas are then marked with ancient symbols allowing the workers to track which barrels contain which wines. Only after at least three years of such fractional blending can it be called Sherry. When the mosto enters the Bodega it is classified by quality, the most refined being selected for Fino and the bigger, bolder wine being selected as Oloroso. From there this Mosto will begin its journey to maturity. Some of this will become wine that will be bottled and released within 3 years and some of it may wind up aging and aging for generations and not be released until it is 100 years old. Whatever the case, it will always remain in its Botas and never be bottled until it is ready to be shipped.  The result of this traditional type of aging, required by the Consejo Regulador, is a wine with great power that remains subtle and elegant. This is a wine that has been governed by strict regulations for centuries which were codified in 1483. Over time these regulations have been changed and adjusted but have remained fixed now for almost 200 years. This is a wine that accompanied Columbus on his great voyage of discovery, a wine that captured the hearts and minds of the court of Elizabeth I of England after the sack of Cadiz in the late 16th Century, and a wine that was an absolute necessity in the fine parlors throughout Europe during the 19th and 20th centuries. No matter how you look at it, Sherry/Jerez/Xerez is a wine that is irreplaceable and unrepeatable. |

AuthorPeter De Trolio III Archives

April 2013

CategoriesAbout the Author

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed